Venezuelan Oil: Statism to Liberation?

By Allen Brooks -- January 6, 2026“Venezuelan oil has been powering Cuba’s electricity grid, and the Trump administration may use the fuel issue to effect changes in the island-nation’s leadership.”

“More heavy oil from Venezuela will put pressure on Canada’s role as a supplier of heavy crude to the U.S. It may also pressure Saudi Arabia, which ships heavy oil to feed its refineries in the U.S.”

“Access to Venezuela’s substantial oil reserves is likely to put a cap on how high global oil prices might rise in the future….”

Little did we realize how interesting 2026’s energy market would become when we finished writing our January 3 Energy Musings, “Energy Finishes 2025 In 8th Place Out Of 11 Sectors.” Just a few hours after finishing and scheduling its publication, United States Special Forces and Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, supported by military forces, mounted a military-style campaign to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores.

Their arrest was to comply with a federal indictment in New York for narco-terrorism conspiracy and other charges. Those charges included cocaine importation conspiracy, possession of machine guns and destructive devices, and conspiracy to possess machine guns and destructive devices.

Multi-Country Ramifications

This dramatic change will have implications for global oil markets. And it might be asked if the political change underway in Venezuela marks the first domino of totalitarian regimes to fall, especially given the growing anti-government protests in Iran.

There will be many geopolitical ramifications from the Venezuelan leadership change, including the termination of sanctions on Venezuela and its oil. President Trump indicated a willingness to sell oil to China, helping Venezuela to pay down its $60 billion debt to that country.

Regionally, removing Maduro ensures that the border dispute with Guyana, which could impact its oil development, will be a non-issue. The news for Cuba, however, is not as favorable. Venezuelan oil has been powering Cuba’s electricity grid, and the Trump administration may use the fuel issue to effect changes in the island-nation’s leadership. That would be consistent with the administration’s desire to enforce the Monroe Doctrine’s policy of preventing foreign intervention in the governments of the Americas. Russia and Iran have long been supporters of the Cuban regime, as well as the Venezuelan regime. Putting these U.S. adversaries on notice to stop meddling in South American politics is an essential message from the Trump administration’s police action dealing with Maduro and his wife.

The decision to allow Venezuela to sell oil to China ensures that the nation will retain its commercial relationships, which are essential for ongoing international business activity. At the same time, it is a signal to China that the U.S. will enforce the Monroe Doctrine policies, removing the Americas as a focal point for increased Chinese involvement, which has involved significant investment in mines, ports, and other South American industries. The move also puts China on notice that its Venezuelan oil flows could be shut off instantly over unfriendly actions towards the U.S., changing the energy landscape for China. This risk may explain why China has been building its oil inventories despite flagging oil demand.

Oil Reserve Markup

Venezuela is estimated to have 303 billion barrels of crude oil reserves as of 2023, 17% of proven world reserves. Significantly, the reserve estimate was increased during the Chávez regime from 80 billion barrels to 303 billion barrels. While the reserve write-up was audited by the petroleum engineering company, Ryder Scott, it was prepared for the Venezuelan dictatorship.

The primary challenge for Venezuelan crude oil is its heavy, sour nature. That makes the oil a lower-quality supply, selling at a discount from world prices. Much of the oil comes from the Orinoco belt, which requires it to be mixed with diluent to enable transportation and refining. That also lowers the oil’s value and creates logistical issues, because without the diluent, the oil cannot be converted into a commercial product. Securing diluent supplies has been a recurring logistical and financial challenge, and is unlikely to change materially in the near term.

Four Oil Charts

Based on data from the Energy Institute and from BP, we have created several charts that show the role of Venezuelan oil in the global oil mix and the nation’s significance within OPEC since 1965. Venezuela was a founding member of OPEC in 1960 because it feared becoming a victim of international oil companies, which were unwilling to pay a fair price for oil extracted from OPEC member countries. [Ed note: The U.S. Mandatory Oil Import Program in 1959 created an oil surplus that sent prices down.]

It took more than a decade for the oil supply pendulum to swing in favor of OPEC members. When it did in the early 1970s, the international oil industry changed dramatically, with pricing power shifting into the hands of the host producing countries. In contrast, countries with mature production risked supply shortages and costly alternatives.

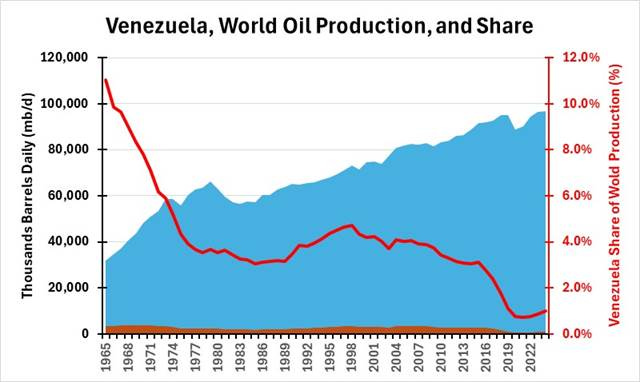

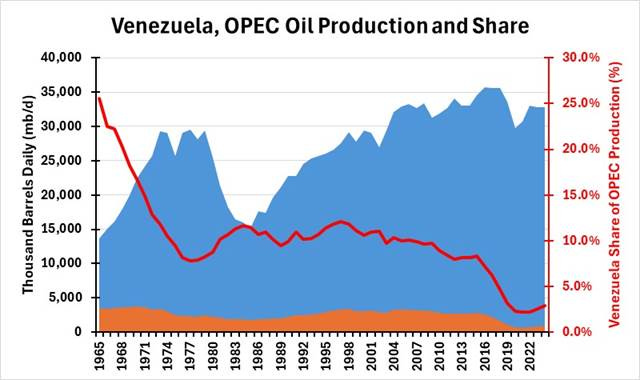

The first two charts show that Venezuela was a more important source of global and OPEC oil supplies in the 1960s and 1970s than it is today. They also show how Venezuela’s market share has declined sharply in recent years. What the charts show is how Venezuela’s output and market share fell sharply during those early years as other OPEC members rapidly expanded their outputs. Moreover, with lower-quality oil, Venezuelan supplies were less desirable to refiners seeking more low-sulfur, light crude oil to convert into gasoline and diesel fuels for the transportation market.

During that period of declining market share, the industrialized world was shifting its electricity generation away from oil to coal and natural gas, reducing the market potential for Venezuelan crude. Remember that this market shift was driven by a change in global oil pricing, from international oil companies to the Middle East OPEC host countries.

Chart 1: Venezuela’s global market share fell by nearly two-thirds between 1965 and 1977.

Chart 2: Venezuela has struggled to sustain relevance within OPEC in recent years.

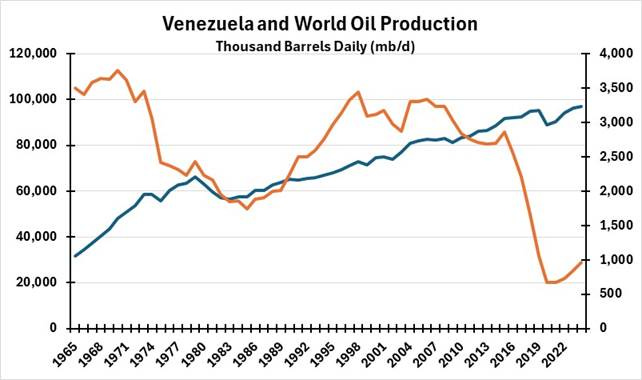

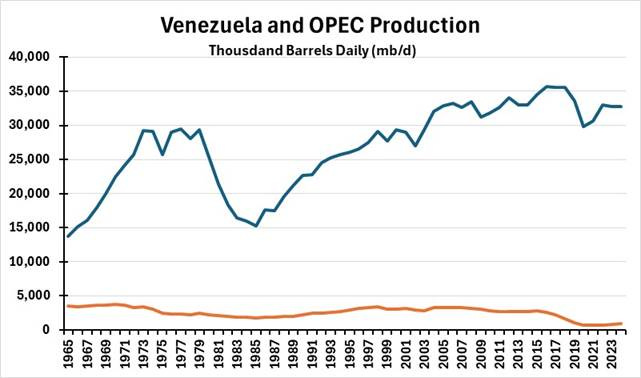

For readers who prefer more granular oil production data, the following two charts show Venezuela’s output relative to the world oil supply and OPEC’s output. The challenges of sustaining and growing its oil production reflected the dynamics of Venezuela’s political situation and the tactics of its national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA).

Hugo Chávez assumed the Presidency of Venezuela on February 2, 1999. At that time, world oil markets were in turmoil, partly due to PDVSA policies to maximize output, disregarding OPEC quotas and price objectives. This was a major contributor to the 1998 oil price collapse. The prior Venezuelan government had nearly abandoned OPEC as it struggled to avoid a financial collapse.

Chávez and his new oil minister, Ali Rodriquez Araque, completely reversed the situation. Along with the governments of Mexico and Saudi Arabia, a new understanding on quotas and higher prices was negotiated between OPEC and other oil-exporting countries.

A bit of personal history. In late February of 1999, as President of the National Association of Petroleum Investment Analysts (NAPIA), we were part of a group invited by PDVSA to spend a week touring Venezuela’s oil industry. PDVSA officials were hoping to curry favor from the investment community, as it would need to tap financial markets to sustain and grow its operations.

To appreciate the charade the Venezuelan government was attempting to conduct, on our first day’s lunch, Oil Minister Ali Rodriquez spoke. A condition was that he would talk in Spanish. Fortunately, we had a member fluent in Spanish who volunteered to conduct a contemporaneous translation. Sitting at the head table with other leaders of NAPIA and me was the U.S. Ambassador. When Rodriquez finished his talk and the Q&A, he sat down and conversed in perfect English with the Ambassador.

The new agreement between OPEC and other oil exporters led to a dramatically different oil market starting in 2000. That year’s Venezuelan oil export revenues were a record of $27.3 billion, a significant increase above the previous peak of $19.1 billion in 1981. However, there was a substantial difference in the impact on the Venezuelan government’s take. In 1981, PDVSA’s $19.1 billion in revenues generated $13.9 billion in royalties and income taxes. In 2000, the $27.3 billion in oil export proceeds generated only $11.3 billion in government income. Royalties and income taxes amounted to 73% of export revenues in 1981, but only 41% in 2000. This shift was mainly due to changes in how PDVSA structured its agreements after 1989, when it opened up its marginal oil fields to international oil companies. Those contracts were structured as service contracts rather than production agreements.

Furthermore, in 1989, when Venezuela came close to insolvency and was forced to subscribe to International Monetary Fund and World Bank adjustment programs and reforms, PDVSA adopted the worldwide accounting rules for reporting profits and losses. This brought down the ring fence around PDVSA’s Venezuelan operations. It was forced to transfer to Venezuela the costs it incurred in its foreign ventures, thus increasing the profits deemed to have accrued outside the country. The difference in tax rates between Venezuela and the United States was 67.7% versus 34%. Moreover, PDVSA also charged its Venezuelan accounts with the financial costs of its nine billion dollars in foreign debt, further reducing domestic profits and the taxes it owed to the Venezuelan government.

Chart 3: Despite its best efforts to increase production, oil output has been in a free-fall.

Chart 4: Venezuela (in gold) remains a minor player in OPEC.

Given the unsettled leadership situation in the government, we should not expect any near-term change in the oil market from Maduro’s removal. At the moment, his vice president, Delcy Rodriguez, has assumed leadership of the country. Unless the military leaders shift their allegiance away from her to the popularly elected politicians in 2024, the current turmoil is likely to continue. Will this lead to a further exodus of Venezuelans, or will people be willing to become active in demanding the leadership they desire?

An Oil Revival?

In the longer term, if the leadership changes to that of popularly elected officials, we can expect Western oil companies to re-enter Venezuela. There is also the possibility that PDVSA will be able to rehire prior professional employees who emigrated rather than live under the Chávez and Maduro regimes. A return of Western oil companies, with their technical talent and financial resources, plus long working histories and knowledge of the country’s oil resources for some companies, will put Venezuela on a path to increased oil output. Estimates are that the sector needs investments of $10 billion a year for many years to restore the industry’s productive capacity.

Few people know the condition of the country’s oil fields, its transportation network, and refining capacity. There may need to be a significant investment before production growth can be achieved. How long will this take, and what price will the international oil companies demand to return to Venezuela? Those are impossible questions to answer now.

While we may be surprised by how quickly the domestic oil industry changes and improves, without a significant number of former PDVSA workers returning, it is safer to expect a long, slow improvement in Venezuela’s production growth. There may be a jump of 250,000 barrels a day in output, assuming PDVSA can acquire sufficient diluent. However, sellers may be reluctant to commit to PDVSA until political stabilization is achieved.

More heavy oil from Venezuela will put pressure on Canada’s role as a supplier of heavy crude to the U.S. It may also pressure Saudi Arabia, which ships heavy oil to feed its refineries in the U.S. China might become a buyer of Canadian and Saudi heavy oil output in the future, as a supply diversification move, further altering global supply chains.

Access to Venezuela’s substantial oil reserves is likely to put a cap on how high global oil prices might rise in the future, given the lack of industry reinvestment in recent years. That could be a good thing for the industry in the long term, as demand might grow more than the International Energy Agency predicts by 2050, with lower near-term oil prices.

The issue of energy dominance is a key outcome of the weekend’s events in Venezuela. Europe struggles to understand it, while China and the U.S. fully comprehend its significance. Russia and Iran are in the process of learning the new energy landscape. Everyone will need to rethink their views of the geopolitical and energy landscapes after last Saturday night’s events.

————–

G. Allen Brooks has been actively engaged in the oil patch in various roles for the last half-century. He has been an energy securities analyst, an oilfield service company manager, a consultant to energy company managements and a director of various oilfield service companies.

Since early 2005, Mr. Brooks has been engaged in consulting as an advisor to PPHB LP, a boutique oilfield service investment banking firm, where he provides proprietary research for the firm’s partners and analysts. PPHB also distributes Musings From the Oil Patch, the highly regarded energy newsletter authored by Mr. Brooks since 1999.

An Economics graduate of the University of Connecticut, Brooks also has an M.S. degree in Economics from Cornell University. He started his investment career in 1969. Mr. Brooks lives in Houston, Texas.

Energy Musings contains articles and analyses dealing with important issues and developments within the energy industry, including historical perspective, with potentially significant implications for executives planning their companies’ future.

Thanks for this interesting piece.

CITGO’s Lake Charles refinery may have just become more valuable.

Thanks again. Your perspective adds value to MR.

Very informative and experiential.

As you noted, more Venezuelan barrels on the market would increase competition for these refineries and possibly those in the American Midwest. This could push down the price premium currently enjoyed by Canadian heavy crude, such as Western Canadian Select. In this sense, Venezuela’s return would not simply add supply; it would challenge Canada’s niche in the U.S. oil import market.

A perceived opening in Venezuela could redirect some international investments away from Alberta’s oilsands. Alberta may find itself competing not just with renewables, but with other oil producers closer to U.S. markets. This could play in favour of an additional pipeline to Canada’s West Coast to reach China, which may not see so many shipments from Venezuela, especially if the U.S. pressures Caracas to privilege its own market and companies.

All of this, however, rests on a big “if.” A rapid and large-scale revival of Venezuela’s oil sector is improbable. Years of mismanagement, underinvestment and sanctions have left infrastructure in poor condition. But energy markets reward stability more than ideology, and regime change rarely delivers it quickly.